P

eople often say to me, ‘You’re a beekeeper, you’re saving the bees!’ which is like telling a chicken farmer they are saving wild songbirds. The ‘save the bees’ mantra came out of the US a few years ago, where commercial honeybee colonies trucked between states to pollinate vast fields of mono-crops started dying in higher numbers than they used to.

Honeybees in the UK are doing OK by comparison. It’s the 250 plus other species of wild bee trying to make it on their own that need our help, along with the rest of our pollinating and non-pollinating insects, which are generally in decline (wasps are immensely valuable, too.)

The threat comes from several directions: pesticides and herbicides (sprayed on farms, parks, gardens, golf courses, roadside verges, you name it) and dwindling areas of pollinator-friendly habitat. Beekeeping has surged in popularity in recent years, putting our wild bees under threat from hives of honeybees competing for forage.

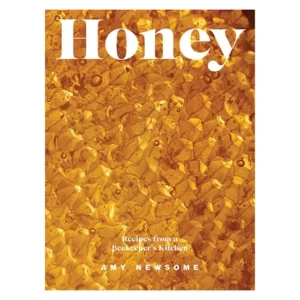

I came into beekeeping and gardening through food, when I started growing my own produce. I was amazed by how much it improved my mental health, but also just how delicious home grown veg is. I took the plunge and changed careers, working and volunteering with amazing organic growers including Anna Greenland at Soho Farmhouse and Jennifer Pryke at Raymond Blanc’s Le Manoir.

Through beekeeping, you become more in tune with how everything is connected in the bloom-to-plate cycle, and the role of insects within it. Having your head at bee level allows you to see burrowing solitary bees and notice that different types of bees visit various types of flower. It’s a very mindful experience and a great privilege.

Moving into formal horticulture at Kew Gardens, I began to understand how our actions in our gardens impact the insects buzzing (or not) around us.

We should care. Pollinating insects are important for our food crops and these ecosystems are the very essence of life. Our actions have consequences, so it’s time to undo the errors that led to this sad decline.

GO WILD

GO WILD