ention ‘breaking’, ‘breaker’, ‘bboy’ or ‘bgirl’ to most and they’ll probably wonder what on earth you’re talking about. But say ‘break dancing’ and it’s guaranteed to evoke an image of kids spinning on their heads to hip hop music.

ention ‘breaking’, ‘breaker’, ‘bboy’ or ‘bgirl’ to most and they’ll probably wonder what on earth you’re talking about. But say ‘break dancing’ and it’s guaranteed to evoke an image of kids spinning on their heads to hip hop music.

While breaking features throughout the media, it’s culture, highly-skilled competitions and physical demands remain a mystery to most. That’s all set to change this summer as it debuts at the Olympics in what will be a testimony to how far breaking has come. This is your chance to get to know what it’s all about.

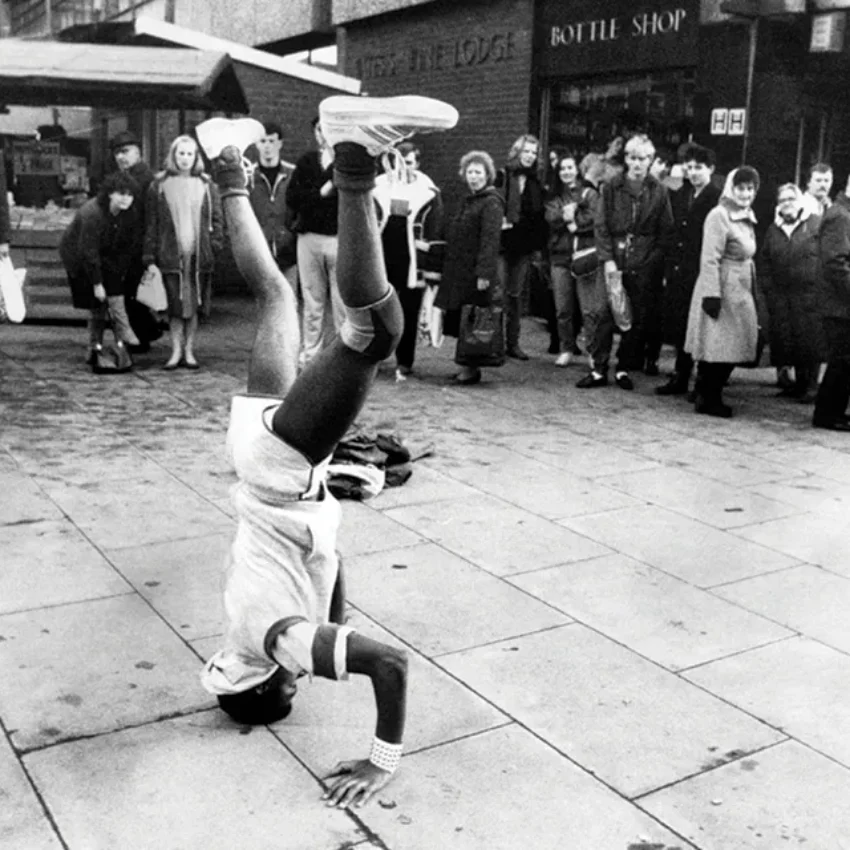

Breaking in the UK

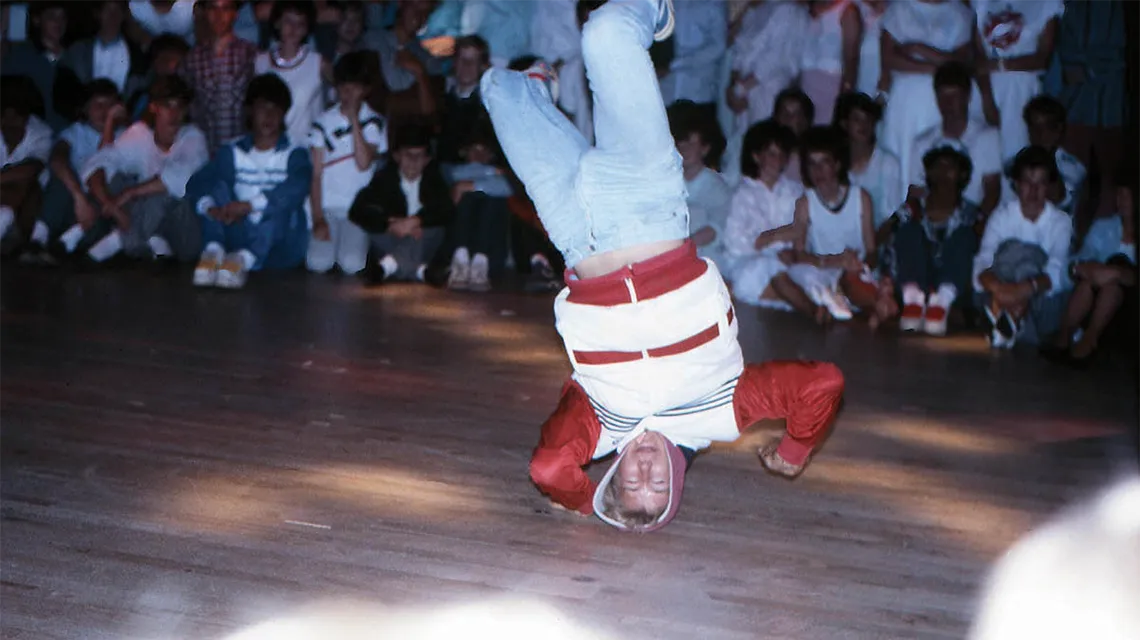

In the 1980’s UK youth became obsessed with the New York born dance of breaking. Dubbed ‘break dancing,’ incorrectly by the media, its popularity was immense. Breakers appeared in news stories, on TV shows and toured with music artists. Then, by the end of the decade, it was over. Then media lost interest and the youth moved on.

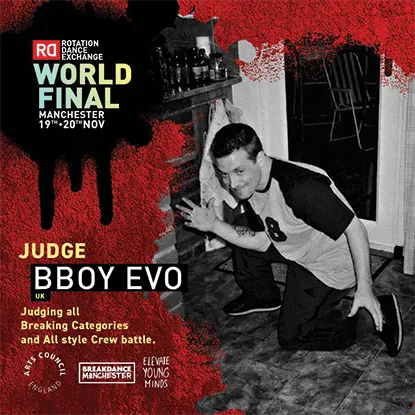

Breaking survived, thanks to a handful of bboys and bgirls competing in ‘battles’ at underground hip hop nights. These events spawned a new era of UK breakers, crews and events; such as the legendary bboy Evo from Manchester, and Bournemouth’s Second to None crew, whose crazy dynamic flows and power moves earned them national and international reputations.

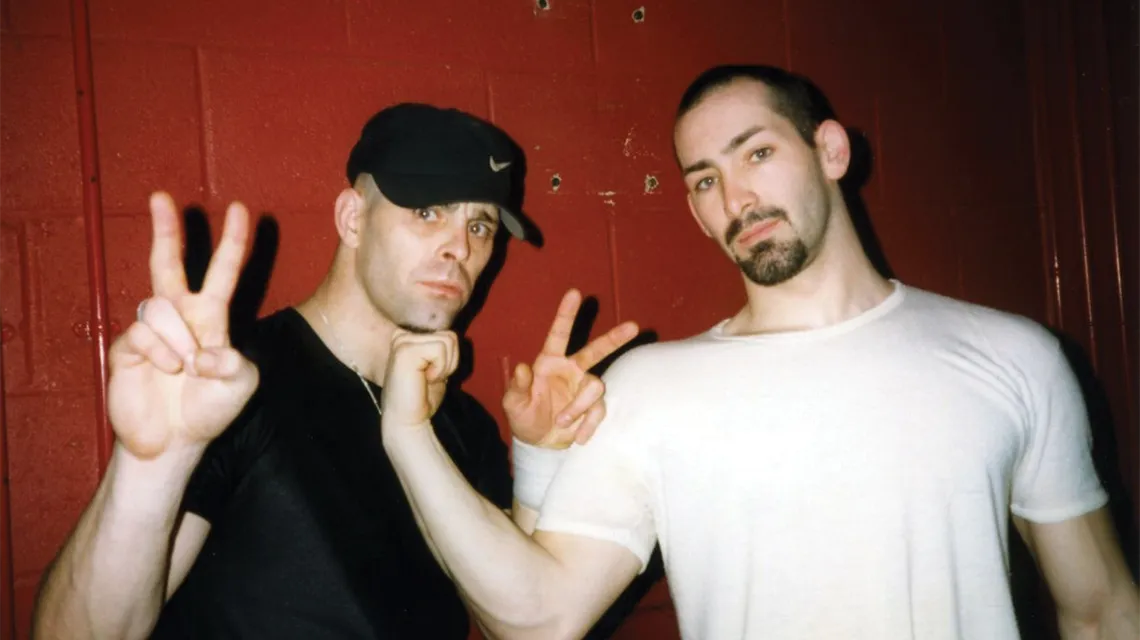

By 1996, the UK BBoy Championships were underway at the Shepherd’s Bush Empire, London. “The venue thought I was a madman who was going to lose all his money,” explains event promoter and DJ Oliver ‘Hooch’ Whittle. “They only gave me the downstairs space that held 750 people – but more than double turned up.”